Kebanyakan ruang kelas prasekolah saat ini terlihat rapi dan terencana dengan baik, tetapi seringkali tidak sesuai dengan tujuannya. Deretan kursi yang identik, meja yang tetap, dan tata letak yang berpusat pada guru tidak mencerminkan cara anak-anak belajar secara alami. Tata letak ini mungkin nyaman bagi orang dewasa, tetapi membatasi kemampuan anak-anak untuk bereksplorasi, berinteraksi, dan berkembang.

Kesenjangan ini menjadi jelas ketika kita melihat melalui sudut pandang Teori Lev Vygotsky, yang menunjukkan bahwa pembelajaran paling baik terjadi melalui interaksi sosial, perancah, dan aktivitas dalam zona perkembangan proksimal anak. Namun, banyak lingkungan kelas justru mengisolasi peserta didik, alih-alih menghubungkan mereka.

Solusinya? Bayangkan kembali ruang kelas bukan hanya sebagai ruang belajar, tetapi juga sebagai ruang pengembangan. Dengan furnitur yang dirancang untuk fleksibilitas, kemandirian, dan interaksi, kita dapat membangun lingkungan yang selaras dengan cara anak-anak belajar—dan di situlah teori Vygotsky dan desain ruang kelas yang bijaksana berpadu.

Perkenalan

Teori Lev Vygotsky, juga disebut Teori Sosiokultural Perkembangan Kognitif, mengubah cara kita memahami pembelajaran. Alih-alih memandang anak-anak sebagai penerima informasi yang pasif, Vygotsky menunjukkan bahwa anak-anak belajar paling baik ketika berinteraksi dengan orang lain dalam lingkungan yang kaya dan responsif.

Dalam artikel ini, kita akan membahas bagaimana gagasan Vygotsky membentuk kembali pendekatan kita terhadap pendidikan anak usia dini—dan bagaimana gagasan ini dapat tercermin dalam tata letak fisik ruang kelas. Anda akan mempelajari:

- Apa konsep inti Vygotsky dan mengapa konsep tersebut penting

- Cara menerapkannya di lingkungan prasekolah dan taman kanak-kanak

- Bagaimana pilihan furnitur Anda dapat mendukung atau menghambat perkembangan anak

Bagi para pendidik, pemimpin sekolah, dan profesional pembelajaran anak usia dini, ini lebih dari sekadar teori—ini adalah panduan untuk membangun kelas yang mendukung pertumbuhan, keterlibatan, dan pembelajaran seumur hidup.

Apa itu Teori Lev Vygotsky?

Teori Lev Vygotsky adalah tentang bagaimana anak-anak belajar melalui orang, bukan hanya kertas.

Vygotsky percaya bahwa anak-anak tidak berkembang secara terpisah. Mereka tumbuh melalui interaksi sosial, seperti berbicara dengan orang dewasa, bermain dengan teman, atau mendengarkan cerita. Ia menyebut proses belajar ini sosiokultural karena dibentuk oleh masyarakat dan budaya.

Bagian penting lainnya? Bahasa. Menurut Vygotsky, bahasa lebih dari sekadar kata-kata—melainkan bagaimana anak-anak belajar berpikir. Saat seorang anak bertanya, "Mengapa?" atau "Apa itu?", mereka tidak hanya mengobrol; mereka sedang membangun pemahaman mereka tentang dunia.

Jadi, ketika kelas dipenuhi dengan percakapan, tugas bersama, dan eksplorasi yang dipimpin anak, itulah ruang yang selaras indah dengan Teori Lev Vygotsky.

Siapakah Lev Vygotsky?

Lev Vygotsky adalah seorang psikolog dari Rusia awal abad ke-20. Dia tidak berumur panjang—hanya 37 tahun—tapi wow, dia meninggalkan dampak yang luar biasa.

Sementara yang lain mengukur apa yang anak-anak tidak bisa namun, Vygotsky fokus pada apa yang mereka bisa, terutama dengan sedikit bantuan. Ia memperkenalkan dua gagasan hebat: Zona Perkembangan Proksimal dan perancah. Kita akan membahasnya sebentar lagi—tapi peringatan: keduanya masih digunakan di ruang kelas modern saat ini.

Karyanya menggeser fokus dari nilai dan tahapan ujian ke sesuatu yang lebih manusiawi: hubungan, budaya, dan dukungan. Dengan kata lain, Vygotsky membantu kita memandang anak-anak bukan hanya sebagai pembelajar, tetapi sebagai manusia kecil yang tumbuh melalui koneksi.

Apa yang Membuat Teori Vygotsky Unik dalam Pendidikan Anak Usia Dini?

Di antara semua teori perkembangan anak, Teori Lev Vygotsky menonjol karena sangat menghormati dunia sosial dan emosional pembelajar muda. Sementara banyak pendekatan pendidikan berfokus pada tahapan, skor, atau daftar periksa, Vygotsky memandang pembelajaran sebagai sesuatu yang sangat manusiawi, bersama, dan berkembang.

Jadi, apa sebenarnya yang membuat teorinya begitu unik—dan masih relevan hingga saat ini?

Mari kita uraikan menjadi tiga ide inti yang terus membentuk cara prasekolah modern mengajar, mendesain ruang, dan mendukung perkembangan awal.

Fokus pada Sifat Sosial Pembelajaran

Inti dari Teori Lev Vygotsky adalah kebenaran yang sederhana namun kuat ini: pembelajaran tidak terjadi secara terpisah.

Anak-anak belajar melalui orang lain. Mereka mengamati, meniru, bertanya, dan memecahkan masalah bersama. Entah itu menyusun balok berdampingan atau bernegosiasi siapa yang mendapat krayon merah, interaksi inilah yang mendorong pertumbuhan.

Inilah yang membedakan Vygotsky—ia tidak memandang belajar sebagai aktivitas yang tenang dan sendirian. Sebaliknya, ia percaya bahwa interaksi sosial mendorong perkembangan, terutama di usia dini. Itulah sebabnya seorang anak yang berbicara dengan guru atau bereksplorasi dengan teman sebayanya bukanlah membuang-buang waktu—melainkan justru cara mereka membangun pemahaman.

Jika ruang kelas Anda memungkinkan percakapan, pergerakan, dan kolaborasi, Anda sudah menjunjung tinggi prinsip ini. Jika tata letaknya membatasi hal itu? Mungkin sudah saatnya untuk mempertimbangkannya kembali.

Penekanan pada Pengembangan Bahasa dan Pikiran

Dalam pandangan Vygotsky, bahasa bukan sekadar cara berbicara—melainkan cara anak belajar berpikir.

Sejak anak bertanya "mengapa" atau menjelaskan apa yang sedang mereka lakukan, proses berpikir mereka sedang terbentuk. Itulah sebabnya mendongeng, bermain pura-pura, dan diskusi kelompok tidak hanya menyenangkan—tetapi juga penting untuk perkembangan kognitif.

Teori Lev Vygotsky menjelaskan bahwa berbicara berawal sebagai alat sosial dan secara bertahap menjadi internal. Pertama, anak-anak berbicara keras untuk membimbing diri mereka sendiri. Kemudian, ini berubah menjadi berpikir dalam hati. Jadi, ketika Anda mendengar seorang anak membisikkan instruksi kepada dirinya sendiri, itu bukan gangguan; itu adalah pembelajaran yang sedang berlangsung.

Hal ini menunjukkan sesuatu yang penting tentang ruang bermain anak usia dini: ruang bermain perlu mendorong perkembangan bahasa. Sudut baca yang nyaman, area bermain peran, dan dialog antara guru dan anak harus menjadi bagian dari kehidupan sehari-hari. Dan ya, bahkan furnitur—seperti tempat duduk rendah untuk obrolan kelompok kecil atau pajangan buku setinggi mata—berperan dalam mendukung perkembangan ini.

Guru sebagai Fasilitator, Bukan Instruktur

Di banyak kelas tradisional, guru berdiri di depan. Para siswa duduk diam, mendengarkan, dan mengikuti. Namun, Vygotsky memiliki visi yang berbeda.

Ia percaya bahwa guru seharusnya bertindak lebih seperti pemandu atau fasilitator—memberikan dukungan secukupnya untuk mendorong anak maju, lalu mundur ketika mereka siap mencoba sendiri. Pendekatan inilah yang sekarang kita sebut perancah, dan merupakan salah satu penerapan Teori Lev Vygotsky yang paling praktis.

Di kelas nyata, ini bisa terlihat seperti:

- Seorang guru duduk di samping seorang anak saat bermain, dengan lembut mendorong pemikiran mereka dengan sebuah pertanyaan.

- Membantu kelompok kecil bertukar pikiran sebelum minggir dan membiarkan mereka mengeksplorasi.

- Mengamati terlebih dahulu, lalu menawarkan bantuan hanya ketika benar-benar dibutuhkan.

Lingkungan kelas harus mencerminkan peran ini. Tata letak yang terbuka, tempat duduk yang mudah dipindahkan, dan zona yang ramah bagi guru memungkinkan para pendidik untuk bergerak bebas, berpartisipasi, dan mendukung tanpa mendominasi. Desain yang tepat memberdayakan guru untuk mengajar seperti yang diinginkan Vygotsky—dengan membantu, bukan mengendalikan.

Zona Perkembangan Proksimal (ZPD)

Dalam pendidikan anak usia dini, salah satu gagasan paling berpengaruh dari Teori Lev Vygotsky adalah Zona Perkembangan Proksimal, yang umumnya dikenal sebagai ZPD. Teori ini menawarkan cara ampuh untuk memahami "titik manis" pembelajaran, di mana anak-anak diberi tantangan yang cukup untuk berkembang, tanpa merasa kewalahan.

ZPD mewakili kesenjangan antara apa yang dapat dilakukan anak secara mandiri dan apa yang dapat mereka capai dengan bimbingan. Saat mengajar, kuncinya bukanlah memberikan solusi, melainkan memberikan dukungan yang tepat untuk membantu anak mencapai tingkat pemahaman selanjutnya.

Apa itu ZPD secara sederhana?

Bayangkan ZPD sebagai tangga. Anak tangga terbawah adalah tugas-tugas yang sudah bisa diselesaikan anak. Anak tangga teratas berada di luar jangkauan anak. ZPD terletak di tengah—anak tangga yang bisa dicapai anak. Bisa memanjat, tetapi hanya jika ada seseorang yang memegang tangga dengan kuat.

Konsep ini menggeser peran guru dari direktur menjadi fasilitator pertumbuhan. Alih-alih hanya berfokus pada apa yang diketahui anak, pendidik yang menggunakan ZPD berfokus pada apa yang siap dipelajari anak. Berikutnya.

Yang terpenting, ZPD tidak statis. Ia berubah setiap hari, bahkan setiap jam. Kualitas dinamis inilah yang menjadikannya alat yang sangat berharga di lingkungan prasekolah, di mana perkembangan terus bergerak.

Mengapa Zona Perkembangan Proksimal Penting

Beradaptasi dengan Ambang Pembelajaran Individu

Dua anak mungkin tampak memiliki tingkat keterampilan yang sama, tetapi memiliki kesiapan yang berbeda untuk tantangan berikutnya. ZPD mendorong para pendidik untuk mengamati dengan saksama dan merespons dengan tepat, alih-alih menerapkan pendekatan seragam.

Dengan mengenali zona belajar proksimal setiap anak, para pendidik dan pengasuh dapat menawarkan kegiatan yang tidak terlalu mudah atau terlalu sulit, tetapi dirancang untuk mengembangkan kemampuan tepat melampaui tingkat saat ini.

Merancang Kegiatan yang Mendorong Kemajuan

Alih-alih pusat pembelajaran statis, kelas dapat menampilkan tugas-tugas berjenjang, seperti teka-teki dengan tingkat kesulitan yang bervariasi, menghitung manik-manik, atau cerita dengan tingkat kerumitan bahasa yang berbeda-beda. Hal ini memberi anak-anak kesempatan untuk memilih sendiri tingkat kesulitan mereka sekaligus mendorong mereka untuk berkembang lebih jauh dengan bantuan ringan.

Pendekatan ini tidak hanya meningkatkan pertumbuhan kognitif tetapi juga mendorong pengambilan keputusan dan kepercayaan diri, karena anak-anak secara bertahap belajar cara menilai kesiapan mereka.

Belajar Melalui Orang Lain

ZPD menekankan bahwa pembelajaran adalah sosialTerkadang, dukungan datang dari guru. Di lain waktu, dukungan datang dari teman sebaya yang sedikit lebih cakap. Anak-anak yang bekerja sama sering kali mengembangkan kemampuan yang sebelumnya terpendam dalam aktivitas individu.

Itulah sebabnya kelas prasekolah yang selaras dengan pemikiran Vygotsky mempromosikan permainan kolaboratif, interaksi teman sebaya, dan eksplorasi kelompok kecil yang dipandu.

Contoh Nyata ZPD di Usia Prasekolah

ZPD bukan hanya teori. Begini tampilannya dalam praktik:

Meja Teka-teki dengan Tingkat Kesulitan Berskala

Seorang guru mengajak seorang anak untuk berpindah dari puzzle 4 keping ke puzzle 8 keping. Anak itu ragu-ragu. Guru memberikan pertanyaan lembut seperti, "Bisakah kamu menemukan sudut-sudutnya?" Sedikit demi sedikit, anak itu menyelesaikan tugasnya. Seiring waktu, perancahnya memudar, dan keberhasilan pun tercapai.

Pembelajaran Peer-to-Peer dengan Blok

Dua anak membangun menara. Satu anak secara intuitif menyusun menara untuk menjaga keseimbangan, yang lain kesulitan. Anak yang lebih berpengalaman berkata, "Yang besar diletakkan di bawah." Sebuah perintah sederhana menciptakan lompatan nyata dalam pembelajaran—inilah bentuk partisipasi terbimbing yang terbaik.

Menulis Selama Bermain Pura-pura

Di area bermain dramatis, seorang anak ingin menulis menu tetapi tidak yakin caranya. Guru ikut serta, membantu melafalkan kata "cokelat". Ini adalah momen yang rendah stres dan berhadiah tinggi yang membangun literasi melalui perancah berbasis permainan.

Zona Matematika dengan Pilihan Terbuka

Di pojok matematika, tugas-tugas disusun berdasarkan tingkat kesulitan. Anak-anak memilih tugas yang mereka rasa tepat, mulai dari menghitung benda hingga mencocokkan pola. Kebebasan bereksplorasi ini, dengan materi yang sengaja dikurasi sesuai tahap perkembangan, menciptakan lingkungan yang mandiri.

Pengambilan Risiko dalam Bermain di Luar Ruangan

Di taman bermain, seorang anak yang ragu-ragu memperhatikan temannya melompat dari peron. Dengan dorongan lembut dari seorang guru—"Kamu boleh turun dulu kalau mau"—anak itu mengumpulkan keberanian, mencoba, dan berhasil. ZPD emosional beraksi.

Mendesain untuk ZPD dengan Furnitur dan Lingkungan

Lingkungan fisik memainkan peran yang tenang namun penting dalam mendukung ZPD. Ruang kelas dapat dirancang agar anak-anak dapat mengakses zona belajar mereka secara mandiri:

- Rak rendah mempromosikan aktivitas yang diarahkan sendiri.

- Meja dan tempat duduk yang dapat disesuaikan mendukung kolaborasi antarteman;

- Beberapa tingkat kompleksitas tugas mendorong penilaian diri dan pilihan.

Kapan furnitur dan tata letak dirancang dengan mempertimbangkan ZPD, kelas menjadi lebih dari sekadar tempat duduk—kelas menjadi peserta aktif dalam perjalanan belajar setiap anak.

Perancah dalam Pendidikan

Salah satu penerapan Teori Lev Vygotsky yang paling praktis adalah konsep perancah—sebuah pendekatan fleksibel yang diterapkan dari waktu ke waktu untuk membantu anak mencapai tujuan pembelajaran berikutnya. Berbeda dengan instruksi yang kaku, perancah menyesuaikan diri berdasarkan kebutuhan anak yang terus berkembang, menawarkan bimbingan bila diperlukan, dan menyesuaikan diri seiring dengan perkembangan kemandirian.

Perancah bukanlah metode yang baku. Ini adalah pola pikir. Perancah menuntut para pendidik untuk mengamati dengan saksama, mendengarkan dengan saksama, dan merespons dengan penuh pertimbangan—karena dukungan yang tepat, pada waktu yang tepat, akan membuka pertumbuhan yang tidak akan terjadi jika tidak demikian.

Seperti Apa Perancah di Prasekolah?

Di ruang kelas prasekolah, perancah ada di mana-mana—jika Anda tahu cara menemukannya.

Guru berlutut di samping seorang anak untuk membantu mereka menutup ritsleting mantel, sambil berkata, "Kamu pegang bagian bawahnya sementara saya tarik." Teman sekelas menjelaskan cara menuang air tanpa tumpah saat waktu camilan. Kelompok itu mengerjakan proyek seni bersama, dengan anak-anak yang lebih tua menunjukkan kepada anak-anak yang lebih muda cara merekatkan bentuk-bentuk.

Momen-momen ini bukanlah gangguan—melainkan jembatan antara apa yang dapat dilakukan anak saat ini dan apa yang hampir siap mereka lakukan.

Perancah adalah cara anak bergerak melalui Zona Perkembangan Proksimal mereka secara real-time.

Strategi Perancah yang Digunakan oleh Pendidik yang Efektif

Pemodelan dan Demonstrasi

Salah satu bentuk perancah paling sederhana adalah menunjukkan cara melakukan sesuatu. Entah itu mengikat tali sepatu, membaca huruf, atau menggunakan gunting dengan aman, anak-anak belajar pertama kali dengan mengamati.

- “Lihat aku memotong sepanjang garis terlebih dahulu.”

- “Dengarkan bagaimana saya menguraikan kata menjadi bunyi: kucing.”

Bentuk pemodelan ini memberi anak-anak suatu titik acuan yang dapat mereka tiru dan hayati.

Mengajukan Pertanyaan Terbuka

Alih-alih memberikan jawaban, guru yang efektif mengajukan pertanyaan yang merangsang pemikiran:

- “Menurutmu apa yang terjadi selanjutnya?”

- “Bagaimana kamu mengetahuinya?”

Dorongan ini mendorong anak-anak ke zona berpikir, di mana otak mereka aktif tetapi tidak kewalahan.

Penyederhanaan dan Pengurutan

Tugas yang tampaknya terlalu rumit dapat dipecah menjadi langkah-langkah yang lebih kecil dan mudah dikelola. Misalnya, daripada mengatakan "Bersihkan seluruh area blok", seorang guru dapat mengatakan:

- “Bisakah kamu mulai dengan memasukkan balok merah ke dalam keranjang?”

Ini mengurangi beban kognitif dan membangun rasa penguasaan.

Menggunakan Isyarat Visual dan Verbal

Bagan, kartu bergambar, panduan langkah demi langkah, dan bahasa yang konsisten semuanya berfungsi sebagai dukungan yang tidak mengganggu. Seiring waktu, isyarat-isyarat ini akan terinternalisasi oleh anak, dan kebutuhan akan bantuan orang dewasa pun memudar.

Mengapa Perancah Membangun Kepercayaan Diri

Perancah tidak hanya meningkatkan pembelajaran akademis, tetapi juga memperkuat rasa efikasi diri anak. Ketika anak-anak menyadari, "Aku berhasil!"—bahkan dengan bantuan—mereka mulai percaya bahwa mereka dapat mencoba lebih banyak lagi di lain waktu.

Dimensi emosional ini sama pentingnya dengan perkembangan kognitif. Anak yang merasa didukung cenderung lebih terlibat, bereksplorasi, dan mengambil risiko.

Bagaimana Lingkungan Prasekolah Mendukung Perancah

Perancah tidak hanya bersifat verbal—tetapi juga lingkungan. Tata letak dan mebel di dalam kelas dapat berperan sebagai guru pendamping yang diam, menawarkan dukungan yang dibutuhkan anak tanpa perlu sepatah kata pun terucap.

Lingkungan sebagai Guru Ketiga

Dalam pedagogi yang terinspirasi Reggio, ruang kelas dianggap sebagai "guru ketiga". Filosofi ini sejalan erat dengan gagasan Vygotsky tentang dukungan tidak langsung.

Pikirkan tentang:

- Bahan yang diberi label dengan jelas yang menunjukkan kepada anak-anak apa yang harus diletakkan di mana;

- Rak setinggi mata sehingga anak-anak dapat memilih apa yang mereka butuhkan;

- Zona pembelajaran yang ditentukan yang secara halus menyarankan perilaku yang pantas (sudut yang tenang, stasiun seni yang berantakan, area konstruksi yang bising).

Struktur-struktur ini membentuk perilaku dan pengambilan keputusan tanpa koreksi orang dewasa yang terus-menerus.

Perabotan yang Memungkinkan dan Memandu

Perabotan prasekolah tertentu secara alami mendukung perancah:

- Meja dan kursi yang dapat disesuaikan memudahkan guru untuk duduk sejajar dengan anak selama pengajaran.

- Penyimpanan yang dapat ditumpuk memungkinkan guru untuk merotasikan materi berdasarkan tujuan pembelajaran saat ini, secara bertahap meningkatkan kesulitan.

- Furnitur kolaboratif, seperti meja bundar atau kuda-kuda ganda, mendorong dukungan antarteman, membiarkan anak-anak saling mendukung.

Setiap elemen ruang dapat mendorong atau menghambat pembelajaran. Furnitur yang dirancang dengan baik menjembatani kesenjangan antara kemampuan dan aspirasi.

Perancah dan Teori Lev Vygotsky

Perancah adalah ekspresi langsung dari Teori Lev Vygotsky Berlandaskan pada keyakinan bahwa anak-anak akan berkembang pesat jika diberikan dukungan yang tepat sasaran—dukungan yang memudar seiring bertambahnya kompetensi.

Ia mengakui bahwa:

- Pembelajaran tidaklah linear;

- Dukungan harus dipersonalisasi.

- Alat, bahasa, ruang, dan hubungan semuanya penting.

Baik itu membantu anak mengeja namanya atau mendorong mereka mencoba struktur panjat baru, perancah tidak hanya membangun keterampilan tetapi juga identitas.

Peran Interaksi Sosial dalam Pembelajaran

Dalam Teori Lev Vygotsky, interaksi sosial bukanlah bonus—melainkan fondasinya. Vygotsky berpendapat bahwa semua pemikiran tingkat tinggi berkembang pertama kali di antara orang-orang, dan baru kemudian di dalam diri individu. Ini berarti bahwa belajar, pada dasarnya, adalah pengalaman sosial.

Kelas prasekolah yang memprioritaskan keterlibatan teman sebaya, dialog, dan aktivitas bersama tidak hanya mendorong perilaku yang lebih baik—tetapi juga mengaktifkan pembelajaran itu sendiri. Melalui bermain kooperatif, percakapan, dan tugas kelompok, anak-anak menginternalisasi ide, bahasa, dan norma budaya.

Aktivitas Kelompok dan Pembelajaran Antarteman

Interaksi dengan teman sebaya merupakan salah satu alat paling ampuh di usia dini. Ketika anak-anak terlibat dalam kegiatan kelompok kecil, mereka mengamati strategi, mencontohkan perilaku, dan mempelajari fleksibilitas kognitif.

Bayangkan seorang anak belajar mengelompokkan benda berdasarkan bentuknya. Sendirian, mereka mungkin tidak memahami konsep tersebut. Namun, ketika duduk di samping teman sebayanya yang berdiskusi dengan mereka—"Yang ini segitiga"—gagasan itu akan langsung dipahami. Inilah pembelajaran terbimbing melalui paparan sosial, salah satu kontribusi Vygotsky yang paling berpengaruh.

Perancah teman sebaya, di mana seorang anak mendukung anak lainnya, secara alami mengaktifkan Zona Perkembangan Proksimal. Tidak perlu instruksi orang dewasa—cukup kekuatan interaksi.

Merancang Ruang untuk Komunikasi Alami

Dalam Teori Lev Vygotsky, bahasa lebih dari sekedar keterampilan—itu adalah alat budaya utama untuk berpikir, bernalar, dan belajar. Dan bagi anak-anak prasekolah, bahasa tidak berkembang dalam keheningan; bahasa tumbuh di ruang yang memungkinkan mereka berbicara, bertanya, dan bercerita.

Itulah sebabnya kelas yang benar-benar terinspirasi Vygotsky harus menjadi lingkungan yang kaya bahasa—ruang di mana interaksi verbal sama pentingnya dengan materi di rak.

Mendesain komunikasi alami bukan hanya tentang mengurangi kebisingan. Ini tentang membentuk ruang agar dialog terjadi secara spontan, bukan hanya saat "berkumpul".

Mari kita lihat bagaimana tiga strategi tata letak yang hebat dapat mengubah kelas Anda menjadi lingkungan belajar yang sosial, ekspresif, dan berfokus pada komunikasi.

Tata Letak Terbuka vs. Meja Terisolasi

Ruang kelas tradisional dengan meja-meja tetap yang berderet seringkali menciptakan hambatan visual dan fisik antar siswa. Dalam lingkungan anak usia dini, tata letak ini justru menekan interaksi yang diyakini Vygotsky penting bagi perkembangan anak.

Tata letak terbuka justru sebaliknya. Tata letak ini mengundang:

- Kontak mata di seluruh meja;

- Bahan-bahan yang dibagikan di pusat;

- Gerakan yang mengarah pada percakapan spontan;

- Mobilitas guru untuk penggabungan dan perancah alami.

Ruang terbuka mendorong anak untuk bertanya, mendengarkan teman sebaya, dan menggunakan bahasa untuk berkolaborasi—semua komponen penting dari pengembangan bahasa sosial.

Kelompok Tempat Duduk Fleksibel

Pengaturan tempat duduk yang dikelompokkan—seperti karpet setengah lingkaran, bantal lantai, atau meja putar—memberikan kebebasan kepada anak-anak untuk berpindah di antara komunitas belajar.

Ini mendukung:

- Pertukaran antar teman ("Bagaimana kamu melakukannya?")

- Dialog yang dipandu guru dalam kelompok kecil;

- Kegiatan bergilir yang mendorong percakapan bervariasi.

Lebih baik lagi? Furnitur ringan berskala anak memungkinkan pelajar muda mengendalikan lingkungan mereka, menumbuhkan kemandirian dan memperkuat gagasan bahwa mereka adalah peserta aktif dalam pembelajaran, bukan penerima pasif.

Pojok Percakapan dan Zona Bermain Peran

Beberapa momen pembelajaran yang paling kaya terjadi di sudut yang paling tenang.

Area percakapan yang dirancang dengan baik dapat mencakup:

- Dua kursi kecil saling berhadapan;

- Rak buku rendah dengan kartu emosi atau buku bergambar;

- Pencahayaan lembut dan karpet peredam suara membuat dialog terasa alami.

Demikian pula, ruang bermain dramatis—seperti dapur mainan, toko kelontong, atau kantor dokter—menjadi laboratorium bahasa tempat anak-anak:

- Menemukan peran;

- Berlatih skrip sosial.

- Negosiasikan ide dengan rekan sejawat.

Ruang-ruang ini hendaknya dilengkapi dengan alat peraga dan tanda berisi kata-kata nyata, yang memberikan kesempatan kepada anak untuk menghubungkan bahasa lisan dengan bahasa cetak, salah satu langkah pertama menuju literasi.

Perbandingan Desain: Ruang Komunikasi Tradisional vs. Terinspirasi Vygotsky

Untuk menyoroti bagaimana desain secara langsung memengaruhi potensi komunikasi, berikut perbandingan berdampingan:

| Elemen Desain | Kelas Tradisional | Ruang Terinspirasi Vygotsky |

|---|---|---|

| Tata Letak Tempat Duduk | Baris tetap atau meja tunggal | Cluster terbuka, meja bundar, dan zona lantai |

| Interaksi Bahasa | Sebagian besar guru ke siswa | Dialog antar teman sebaya dan kelompok didorong |

| Peran Furnitur | Statis, berfokus pada orang dewasa | Berukuran anak-anak, mudah dibawa, dan ramah kolaborasi |

| Mode Pembelajaran | Tugas individu | Eksplorasi dan diskusi bersama |

| Akses terhadap Materi | Didistribusikan oleh guru | Alat bersama yang dapat diakses sendiri dan berlokasi terpusat |

| Zona Komunikasi | Satu (hanya waktu lingkaran) | Banyak: sudut yang tenang, drama, zona membaca |

| Peran Guru | Instruktur memberikan arahan | Fasilitator yang mendukung interaksi sosial |

Mengapa Ini Penting

Ketika kelas dirancang untuk mendorong percakapan alami, kelas tersebut menjadi lingkungan dinamis yang mendukung setiap aspek Teori Lev Vygotsky:

- Ia menghargai budaya dan komunitas;

- Ini mendorong bahasa sebagai alat pembelajaran, bukan hanya sekadar keterampilan untuk dipraktikkan.

- Memberikan guru fleksibilitas untuk membimbing tanpa mendominasi;

- Dan memberi anak kebebasan untuk berekspresi, bertanya, dan tumbuh bersama.

Singkatnya, furnitur, tata letak, dan desain dapat memupuk atau membatasi komunikasi. Ruang yang penuh perhatian akan menyampaikan banyak hal, bahkan sebelum anak-anak menyadarinya.

Bagaimana Teori Vygotsky Diterapkan di Kelas Prasekolah

Jadi, bagaimana kita menerjemahkan Teori Lev Vygotsky ke dalam desain prasekolah praktis dan pengajaran sehari-hari? Kuncinya adalah membangun lingkungan yang memungkinkan perancah, pembelajaran antarteman, dan pengalaman yang mendukung ZPD dapat berkembang secara alami.

Ini berarti beralih dari “ruangan yang dihias” menuju ekosistem pembelajaran yang disengaja, di mana ruang, materi, dan peran orang dewasa semuanya beradaptasi dengan tingkat kesiapan anak.

Menciptakan Kelas yang Ramah ZPD

Merancang untuk Zona Perkembangan Proksimal membutuhkan fleksibilitas. Kelas yang ramah ZPD tidak mengasumsikan semua anak berada di halaman yang sama. Sebaliknya, hal ini:

- Menawarkan tugas bertingkat di setiap pusat pembelajaran;

- Dilengkapi dengan alat-alat yang bertingkat (misalnya, teka-teki, arahan seni, alat peraga matematika) sehingga anak-anak dapat menilai diri sendiri dan mengembangkan diri;

- Memiliki organisasi yang jelas sehingga anak-anak dapat menavigasi secara mandiri dan dengan bimbingan.

Misalnya, pusat penulisan mungkin memiliki:

- Kartu kata bergambar untuk pelajar awal;

- Permainan fonik untuk mereka yang sedang dalam masa transisi.

- Potongan kalimat untuk pendongeng tingkat lanjut.

Ini bukan sekadar pedagogi inovatif—ini adalah desain spasial terstruktur yang sedang beraksi.

Mendorong Kemandirian Sambil Mendukung Pertumbuhan

Vygotsky menekankan bahwa anak-anak berkembang paling baik dengan bantuan yang cukup. Dalam konteks kelas, ini berarti:

- Membiarkan anak-anak memilih materi mereka;

- Memberi mereka waktu untuk mencoba dan gagal sebelum melangkah maju;

- Membuat rutinitas yang menumbuhkan rasa kepemilikan, seperti tempat makan ringan swalayan, bagan pembersihan, atau papan pekerjaan.

Perabotan juga dapat mendukung hal ini:

- Penyimpanan setinggi anak-anak mempromosikan otonomi.

- Label visual pada tempat sampah kurangi arahan orang dewasa.

- Pijakan kaki dan zona jangkauan memberdayakan navigasi mandiri.

Bila dirancang dengan baik, kelas itu sendiri menjadi pelatih yang tenang, mendorong anak-anak maju tanpa memaksa terlalu keras.

Mengamati dan Menanggapi Setiap Tahapan Anak

Mungkin hal yang paling Vygotskian yang dapat dilakukan oleh seorang guru adalah mengamatiPerkembangan tidaklah linier, dan tidak ada dua anak yang mencapai tonggak perkembangan pada saat yang sama.

Guru yang mengetahui di mana setiap anak berada dapat:

- Sesuaikan pertanyaan agar sesuai dengan zona pelajar.

- Kelompokkan anak-anak berdasarkan kebutuhan belajar bersama, bukan hanya usia;

- Berikan dukungan seperlunya saja, lalu berikan dukungan lagi saat kepercayaan mulai terbangun.

Ini berarti ruang kelas harus terlihat, mudah dinavigasi, dan mudah dibaca—sehingga orang dewasa dapat dengan cepat mengetahui di mana dan bagaimana cara terlibat.

Mengamati dan Menanggapi Setiap Tahapan Anak

Salah satu prinsip paling penting dari Teori Lev Vygotsky Perkembangan itu tidak seragam. Anak-anak tidak belajar dengan cara yang sama atau dalam jangka waktu yang tetap. Sebaliknya, pertumbuhan mereka berlangsung secara bertahap, dibentuk oleh faktor biologis, lingkungan, budaya, dan terutama interaksi sosial.

Di kelas prasekolah yang didasarkan pada Teori Lev Vygotsky, para pendidik tidak sekadar menyampaikan instruksi; mereka adalah pengamat aktif—mencari petunjuk yang menunjukkan di mana posisi setiap anak dalam Zona Perkembangan Proksimal mereka.

Observasi bukanlah sesuatu yang pasif. Observasi adalah kunci pengajaran yang responsif. Ketika guru mengetahui apa yang dapat dilakukan anak secara mandiri dan apa yang hampir dapat mereka lakukan dengan bantuan, mereka dapat memberikan dukungan terarah yang benar-benar berdampak.

Mengenali Perbedaan Perkembangan Berdasarkan Kelompok UsiaP

Untuk menerapkan Teori Lev Vygotsky secara efektif di lingkungan prasekolah yang nyata, penting untuk memahami bagaimana ekspektasi perkembangan berubah seiring bertambahnya usia. Anak-anak dengan usia yang berbeda membutuhkan bentuk perancah, model bahasa, dan dukungan spasial yang berbeda pula.

Berikut ini adalah rincian perilaku umum dan strategi kelas untuk kelompok usia prasekolah inti:

| Kelompok Usia | Ciri-ciri Perkembangan Khas | Fokus Guru | Rekomendasi Lingkungan & Furnitur |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-3 Tahun | Perkembangan bahasa yang cepat, permainan paralel, keterampilan motorik dasar | Perkembangan bahasa yang cepat, permainan paralel, dan keterampilan motorik dasar | Rak terbuka rendah, manipulatif besar, ruang lembut yang aman, stasiun satu lawan satu |

| 3–4 Tahun | Dorong interaksi antar teman, perkenalkan permainan peran, dan bantulah bercerita | Meja kelompok kecil, furnitur permainan dramatis, dan sudut literasi awal | Membangun pemecahan masalah, mendorong kolaborasi kelompok, dan mengajukan pertanyaan terbuka |

| 4-5 Tahun | Pengendalian diri yang lebih baik, fokus yang lebih luas, penalaran awal, narasi imajinatif | Membangun pemecahan masalah, mendorong kolaborasi kelompok, dan mengajukan pertanyaan terbuka. | Stasiun berbasis tugas, zona tantangan multi-level, sudut menulis dan berpikir |

Jenis struktur kelas yang peka terhadap usia ini selaras sempurna dengan Teori Lev Vygotsky, memastikan lingkungan belajar setiap anak sesuai dengan kebutuhan perkembangan mereka sekaligus menawarkan akses ke tantangan berikutnya melalui perancah yang tepat.

Mengapa Hal Ini Penting bagi Guru dan Desainer

Baik Anda sedang menyusun kurikulum atau mendesain furnitur prasekolah, memahami tahapan perkembangan anak sangatlah penting. Teori Lev Vygotsky mengajarkan kita bahwa pengajaran harus sesuai dengan perkembangan anak, dan melampauinya.

Sebagai contoh:

- Anak berusia 3 tahun dapat memperoleh manfaat dari cerita yang dipandu dengan gambar.

- Anak berusia 4 tahun mungkin tumbuh subur dengan stasiun sains yang kooperatif.

- Anak berusia 5 tahun mungkin terlibat secara mendalam dalam proyek penyelidikan berbasis kelompok.

Semua pengaturan ini memerlukan furnitur yang tidak hanya sesuai usia tetapi juga memperhatikan ZPD—mampu mendukung apa yang dapat dilakukan anak-anak saat ini dan apa yang hampir siap mereka lakukan.

Ketika ruang kelas mencerminkan nuansa-nuansa ini, ruang kelas tidak lagi menjadi ruang belajar generik. Ruang kelas menjadi Laboratorium perkembangan Vygotskian—dirancang untuk kemajuan, didukung oleh observasi, dan dipandu oleh teori itu sendiri.

Menyatukan Semuanya

Prasekolah yang dibangun berdasarkan Teori Lev Vygotsky tidak terlihat kacau, tetapi justru tampak hidup. Anak-anak bergerak, berbicara, berkreasi, dan berkolaborasi. Materi dapat diakses, tidak terkunci. Guru tidak memberikan jawaban—mereka membimbing eksplorasi.

Yang terpenting, setiap anak tidak hanya dilihat berdasarkan siapa mereka saat ini, tetapi juga berdasarkan siapa mereka nantinya.

Dan ketika kelas mencerminkan keyakinan itu—dalam alirannya, perabotannya, dan fleksibilitasnya—warisan Vygotsky menjadi nyata, bukan teoritis.

Ruang kelas impian Anda hanya tinggal satu klik saja!

Teori Pendidikan Bertemu Desain Praktis

Menerjemahkan teori pendidikan ke dalam desain kelas bukan lagi pilihan—melainkan esensial. Dalam lanskap anak usia dini saat ini, para pendidik, perancang, dan pengambil keputusan membutuhkan lingkungan yang secara aktif mendukung perkembangan anak. Among all early learning theories, Lev Vygotsky Theory offers one of the most practical blueprints for building spaces where real learning can happen.

Inti dari Teori Lev Vygotsky adalah konsep bahwa perkembangan terjadi melalui interaksi sosial, dukungan terarah (scaffolding), dan tantangan yang sesuai dalam Zona Perkembangan Proksimal (ZPD) anak. Bagi para desainer furnitur prasekolah, prinsip-prinsip ini bukan sekadar akademis—melainkan fondasi bagi desain yang bermakna dan berpusat pada pertumbuhan.

Bagaimana Perabotan Kita Menanamkan Prinsip Vygotsky

Kami memulai setiap proses desain dengan mengajukan pertanyaan sederhana: "Pembelajaran seperti apa yang dimungkinkan oleh hal ini?" Dengan mempertimbangkan Teori Lev Vygotsky, pertanyaan tersebut mengarahkan kami untuk memprioritaskan fleksibilitas, independensi, kolaborasi, dan visibilitas.

Perancah dalam Bentuk Furnitur

Di kelas yang berakar pada Teori Lev Vygotsky, perancah bukan hanya verbal—melainkan spasial. Furnitur kami mencerminkan hal ini dengan mendukung beragam interaksi guru-anak:

- Materi terbuka memungkinkan anak bereksplorasi dengan atau tanpa bantuan.

- Meja modular mendukung rotasi guru untuk bimbingan waktu nyata.

- Tata letak setengah lingkaran Jaga jarak percakapan anak-anak dengan orang dewasa dan teman sebaya.

Desain-desain ini mencerminkan keyakinan Vygotsky bahwa pembelajaran bersifat sosial dan responsif. Seorang anak yang mencoba memecahkan teka-teki di dekat teman sebayanya yang sudah menguasainya seringkali akan belajar lebih cepat daripada hanya melalui instruksi. Stasiun kami menciptakan ruang untuk momen-momen tersebut.

Merancang untuk ZPD

Pembelajaran paling efektif di ambang batas kemampuan. Itulah sebabnya setiap pusat pembelajaran yang kami bangun mencakup:

- Bahan-bahan yang lulus:Aktivitasnya berkisar dari tingkat pemula hingga tingkat lanjut, mendorong anak untuk memilih sendiri berdasarkan kenyamanan dan kepercayaan diri.

- Alat yang dapat dipelajari dengan kecepatan sendiri:Dari manipulatif hingga dorongan literasi, anak-anak memilih apa yang mereka siap untuknya.

- Isyarat visual:Panduan kesulitan atau langkah demi langkah yang diberi kode warna membantu anak-anak mengetahui apa yang akan terjadi selanjutnya.

Menggabungkan unsur-unsur ini memastikan anak-anak tetap berada dalam Zona Perkembangan Proksimal mereka, persis seperti yang diuraikan oleh Teori Lev Vygotsky.

Mendukung Pembelajaran Verbal dan Sosial

Bahasa memainkan peran sentral dalam teori Vygotsky. Itulah sebabnya kami menyematkan kesempatan untuk berbicara dan bercerita di hampir setiap konteks:

- Zona bermain dramatis dengan alat peraga isyarat sosial;

- Meja seni bersama yang mendorong dialog deskriptif;

- Pusat literasi dengan stasiun membaca sejawat dan alat bahasa bergiliran.

Setiap lingkungan mengundang jenis interaksi yang dijelaskan Vygotsky: pembuatan makna bersama dalam tindakan.

Tata Letak Responsif Guru

Kekuatan signifikan dari pendekatan kami terletak pada bagaimana pendekatan ini melayani para pendidik. Guru tidak dapat memberikan perancah secara efektif jika ruangan mengisolasi mereka dari peserta didik. Itulah sebabnya desain kami mencakup:

- Zona guru keliling untuk intervensi yang fleksibel.

- Visibilitas 360° dari posisi kunci;

- Tata letak kesulitan berlapis sehingga materi dapat dirotasi berdasarkan kesiapan belajar, bukan hanya jadwal.

Semua ini membuat perancah lebih mudah, baik yang disengaja maupun tidak disengaja.

Pendekatan kami tidak hanya merujuk pada Teori Lev Vygotsky—tetapi juga memungkinkannya diterapkan di dalam kelas.

Mengapa Desain yang Cermat Mendorong Pertumbuhan Anak

Bukan hanya isi ruang kelas—melainkan bagaimana ruang kelas tersebut berfungsi yang menentukan nilai perkembangannya. Ketika furnitur prasekolah dirancang dengan mempertimbangkan Teori Lev Vygotsky, pertumbuhan menjadi bagian dari infrastrukturnya.

Kemerdekaan Tanpa Isolasi

Vygotsky menekankan keseimbangan yang rumit antara otonomi dan bimbingan. Produk kami mencerminkan hal ini:

- Penyimpanan setinggi anak-anak mendorong pemilihan sendiri.

- Tempat sampah yang transparan dan visual mengurangi ajakan orang dewasa.

- Bangku pijakan, cermin rendah, dan konter swalayan menumbuhkan kesadaran diri dan kepercayaan diri.

Lingkungan memungkinkan anak untuk mencoba, menguji, mencoba lagi—dan akhirnya berhasil.

Pembelajaran Antarteman sebagai Fitur Bawaan

Pembelajaran sosial bukanlah suatu kebetulan—melainkan prinsip inti Teori Lev Vygotsky. Desain kami menyediakan ruang untuk:

- Stasiun pembelajaran bersama yang dapat menampung 2–4 anak;

- Zona berbisik untuk membaca dan bercerita;

- Struktur permainan kolaboratif dengan pembagian peran yang terintegrasi.

Lingkungan mikro ini memungkinkan anak-anak untuk belajar satu sama lain saat mereka bergerak melalui ZPD mereka di berbagai domain.

Adaptasi Dinamis berdasarkan Desain

Perkembangan tidak statis. Itulah sebabnya ruang kelas tetap tidak dapat melayani anak-anak yang fleksibel. Furnitur kami dirancang untuk berevolusi:

- Rak diubah menjadi stasiun.

- Dapur mainan menjadi pusat sains.

- Sudut baca berfungsi ganda sebagai zona pertemuan pagi.

Kami mendukung kebutuhan pembelajaran yang dinamis dengan solusi yang dinamis, semuanya dipandu oleh pola pikir adaptif dari Teori Lev Vygotsky.

Menjadikan Setiap Ruang Kelas Sebagai Ruang Pengembangan

Apa yang mengubah ruang dari dekoratif menjadi ruang perkembangan? Keselarasan dengan pertumbuhan anak. Teori Lev Vygotsky menegaskan bahwa anak-anak adalah konstruktor aktif pembelajaran mereka, dengan bimbingan orang dewasa dan alat yang tepat.

Isyarat Lingkungan yang Mendorong Pertumbuhan

Tiga prinsip memandu setiap ruang yang kami bantu ciptakan:

- Otonomi yang dapat diaksesAnak-anak meraih dan mengembalikan bahan sendiri.

- Perancah sosial:Tata letak mendorong bantuan rekan sejawat dan masukan guru.

- Tantangan kejelasan:Selalu jelas apa yang dapat dicoba anak selanjutnya.

Hasilnya adalah kelas yang berfungsi seperti guru, yang mendorong, mengatur kecepatan, dan mempersonalisasikan pengembangan.

Kelas yang Melihat Masa Depan Anak

Pendekatan kami tidak hanya mendukung pembelajar masa kini. Pendekatan ini mengantisipasi apa yang hampir siap dihadapi setiap anak. Itulah esensi desain yang selaras dengan ZPD.

- Teka-teki terbuka tumbuh bersama anak.

- Pembuka cerita menjadi dorongan menulis.

- Ruang bermain peran berkembang dari imitasi menjadi penemuan.

Beginilah cara Anda membangun kelas yang tumbuh bersama anak-anaknya.

Kesimpulan

Keindahan Teori Lev Vygotsky terletak pada kenyataan bahwa teori tersebut tidak dimaksudkan untuk hanya ada di buku teks. Teori ini dimaksudkan untuk diterapkan di ruang kelas, dalam interaksi guru, dan di setiap meja dan rak berukuran anak. Ketika kita memahami pembelajaran sebagai proses sosial, terstruktur, dan terus berkembang, pendekatan kita terhadap pendidikan anak usia dini pun berubah dari dalam ke luar.

Ruang kelas yang terinspirasi oleh Teori Lev Vygotsky tidaklah statis. Ruang kelas merupakan ekosistem dinamis tempat pembelajaran berbasis bermain, penemuan terbimbing, dan eksplorasi yang didukung oleh teman sebaya berkembang pesat. Dan bukan hanya kurikulum yang memungkinkan hal ini—melainkan ruang fisik, materi, dan alat yang mengelilingi anak setiap hari.

Para desainer dan pendidik yang berkolaborasi dalam visi ini menciptakan lebih dari sekadar furnitur. Mereka membangun lingkungan prasekolah yang fleksibel di mana pembelajaran ZPD tidak hanya didorong, tetapi juga difasilitasi. Mereka menawarkan perangkat pendukung kognitif yang dapat disesuaikan seiring perkembangan pemahaman anak. Mereka mengubah pengajaran yang disengaja menjadi bahasa arsitektur.

Jadi, apakah Anda sedang mengkurasi sudut literasi, mendesain zona sensorik, atau memilih tempat duduk yang memungkinkan kemandirian dan kolaborasi, biarkan Teori Lev Vygotsky membimbing Anda.

Karena tujuannya bukan hanya untuk memenuhi ruangan—melainkan untuk membentuk sebuah pengalaman. Pengalaman yang sesuai dengan tingkat kemampuan setiap anak, menghargai potensi mereka, dan mendukung langkah mereka selanjutnya—entah itu mempelajari kata baru, memecahkan teka-teki, atau sekadar meraih mainan sendiri.

Pada akhirnya, perkembangan bukanlah hasil kebetulan. Perkembangan merupakan hasil dari lingkungan yang dirancang dengan cermat, peran orang dewasa yang bijaksana, dan interaksi sehari-hari yang menghidupkan teori.

Dan bagaimana jika perabotan prasekolah Anda mencerminkan hal itu?

Anda tidak hanya mendesain—Anda mendukung pertumbuhan anak usia dini di setiap tingkatan.

Tanya Jawab Umum

1. Apa saja 4 prinsip teori Vygotsky?

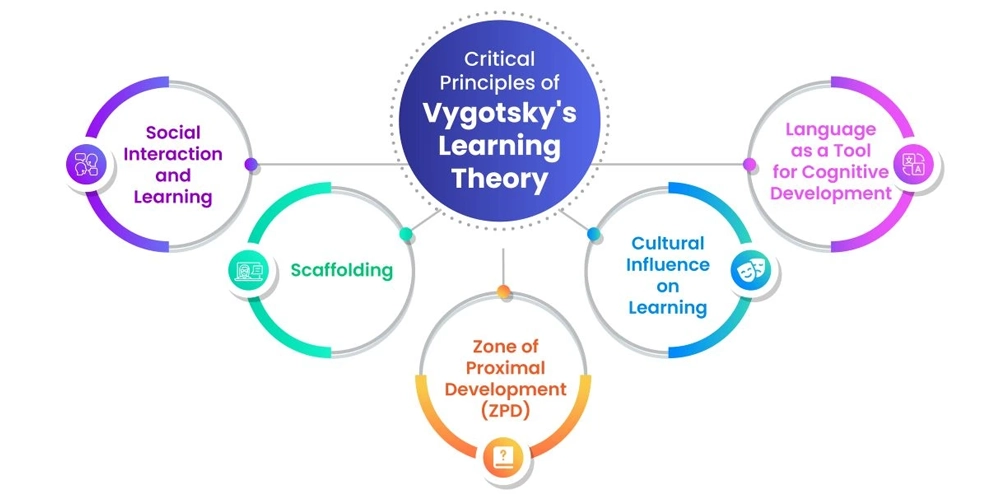

Teori Lev Vygotsky mencakup empat prinsip inti: interaksi sosial mendorong pembelajaran, perkembangan bervariasi berdasarkan budaya, bahasa membentuk pemikiran, dan pertumbuhan kognitif terjadi di ZPD melalui dukungan terbimbing.

2. Apa tiga konsep utama teori Vygotsky?

Tiga ide kunci dalam Teori Lev Vygotsky adalah: Zona Perkembangan Proksimal (ZPD), perancah, dan peran sentral konteks sosial dan budaya dalam perkembangan anak usia dini.

3. Apa saja 5 tahap teori Vygotsky?

Vygotsky menguraikan lima tahap perkembangan bicara dan pikiran: bicara pra-intelektual, bicara otonom, psikologi naif, bicara komunikatif, dan bicara batin—semuanya merupakan inti teori sosiokulturalnya.

4. Apa itu perancah dalam teori Vygotsky?

Perancah dalam Teori Lev Vygotsky adalah dukungan yang diberikan kepada anak-anak saat mereka mempelajari tugas-tugas baru. Perancah membantu menjembatani kesenjangan antara apa yang dapat mereka lakukan sendiri dan apa yang dapat mereka lakukan dengan bantuan, yang penting dalam pembelajaran ZPD.

5. Bagaimana teori Vygotsky berbeda dari teori Piaget?

Tidak seperti Piaget, itu Teori Lev Vygotsky menekankan pembelajaran melalui interaksi sosial. Fokusnya adalah pada penemuan terbimbing, perangkat budaya, dan dukungan orang dewasa atau teman sebaya dalam perkembangan.

6. Apa saja contoh teori Vygotsky di prasekolah?

Contohnya meliputi pembelajaran antarteman, permainan terbimbing, area peran dramatis, dan stasiun aktivitas bertingkat—semuanya mendukung ZPD dan perancah, seperti yang ditekankan oleh teori sosiokultural Vygotsky.

7. Mengapa ZPD penting untuk tumbuh kembang anak?

Zona Perkembangan Proksimal membantu mengidentifikasi rentang pembelajaran yang ideal. Menurut Teori Lev Vygotsky, anak-anak tumbuh paling cepat dengan tantangan yang tepat dan dukungan yang tepat.

8. Bagaimana perabotan prasekolah dapat mendukung pembelajaran sosiokultural?

Perabotan yang selaras dengan Teori Lev Vygotsky meningkatkan interaksi sosial, otonomi anak, dan ekspresi budaya—elemen kunci dalam mendukung perkembangan anak usia dini.